The Illusion of Separation

“Not nurturing the illusion but only overcoming it gives us the attainable measure of inner peace.” - Albert Einstein

Whenever someone asks me about my dad, I need a moment to process the word and connect it to its meaning. It happens in a fraction of a second—imperceptible even in the most fluid of conversations—but enough for me to notice the strangeness of the concept. They mean my father, a “dad” feels like an acquired relationship, one that may not even align with biological paternity. Informal nouns and diminutives carry an implication of affection, and affection is something that develops over time, like the patina that forms on high-quality leather after years of use and exposure.

I didn’t live with my father, so I didn’t grow up with him—not fully. I knew him, I talked to him, I even spent time with him occasionally, but we never became close. When he died, just as he was entering his sixties, I was still a few years away from unlocking the “dad” that my older half-siblings had access to. He tried to be present—as much as he could and knew how—but ultimately he only started to enjoy the company of his children, and youth in general, once they had grown a little. He appreciated them more once they had reached the age of majority and encountered some of life’s pleasures and especially some of its pains. He had neither the time nor the inclination for the energetic cluelessness of the young, and he much preferred the experiences of those who had already ventured outside the walls to the naïveté of the ones still shielded by them. In the end, his inner circle required maturity for membership—a trait rarely achievable at thirteen.

I have no resentment toward him, no associated sadness, no bad memories even, merely an absence of good ones, which is perhaps an already better experience of paternity than many sons can claim. I’ve always understood his difficulty in relating to me, given that I never cared much for youth either, not even when I was going through it. All the way through college, I had almost no overlapping interests with people my age. First loves and first heartbreaks, nights out and hangovers, teen shows and boy bands—all of it seemed to lack the depth that I found in the experiences of teachers, family friends, and the guild mates of the virtual worlds where I definitely spent too much time. That introversion was likely a byproduct of my own uneasiness with myself, and while my peers grew up discovering the perks of being a teenager and testing the limits of their findings, I traded them for forays into the adult mind.

At this point, the realization for me isn’t so much that we can turn into our parents or that the apples don’t fall far from the trees, but that the surrounding orchard can sometimes help bridge the distance between them. My bond with my father has started to pierce through time and space, as I develop the relationship asynchronously and unilaterally, picking up pieces in the writings he left behind and in the stories people tell me about him. The more I learn, the less certain I am about the kind of relationship we might have had: I can imagine it either filled with fiery discussions or marked by nods of agreement or, most likely, a mix of the two. Regardless, knowing what I know, I think that I would have joined the list of those who held him in high regard. My interest in his life and work continues to grow, and I sometimes wonder if it’s possible to tune in to his mind space when I find myself in his old home—a peculiar place where I’m now living for an undetermined period.

It’s a rustic house of brick and concrete, with solid wood furniture and two massive steel beams supporting a slanted dark walnut ceiling. It was built to withstand time, even if reparations have inevitably been made because time touches all things. Very little else has been altered, honoring his wishes for the house to remain a home away from home for loved ones who might come to need it. That’s where I now find myself, over two decades after his death, following a layoff that forced me to leave the U.S. to avoid accruing what the Immigration Service calls “unlawful presence”. He would likely have a lot to say about that term—assuming he would forgive me for moving there in the first place, the land of opportunity that he couldn’t disconnect from its opportunism. Although it was a forced return, it was nevertheless a welcome break from a corporate life that had long been losing its meaning. In rotting times, perhaps the focus should be on preventing further decay, and what is marketing if not an enabler of the pathogen, a defense mechanism for this mind plague of consumption.

If this existential despair was starting to take root in the minimalist, clean-lined, bright studios I was accustomed to on the West Coast, the cozy but penumbral environment of my father’s house only feeds it, as if introspection grows better in the dark. The small windows were not a stance against the sun, the light was never an enemy, it was simply an accepted collateral casualty in the battle against the inland summer heat. It’s not a bad feeling, though, just different, like the one you might get in a temple: as much fresh and welcoming as it is somber and quiet—at least until people come together within. It can be the most lively place when wine flows from dusk to dawn, or it can expose your soul during rainy days if you find yourself alone and untrained in appreciating the life-force of the water.

It didn’t take me too long to adapt, as I’ve always enjoyed being by myself, even when it was harmful. For most of my life, I believed that loneliness was a natural byproduct of being alone, something that I had to accept and suffer through. It isn’t, it’s just a kind of horror vacui, the mind filling the emptiness with fears echoed from a society uncomfortable with the silence. I didn’t remember that Aristotelian concept, nor its reinterpretations by Rabelais and Galileo—or rather we were made to forget them, just like we were made to forget much of the pre-industrial wisdom that could help us in an era of industrialized unhappiness. It now seems obvious to me that the best antidote to loneliness is found precisely in being alone, once the distinction is made and the paradox is resolved. It doesn’t mean avoiding others, it means not avoiding yourself, where purpose is found. The value of aloneness is not in the absence of people—something I’ve learned the hard way should never be prolonged—but in being able to listen to the underlying hum of the discomfort and trace it back to its source.

I realize this kind of wording has all the hallmarks of a platitude from an animation movie, where the power was inside the main character all along, but maybe that’s not such a bad thing. There’s always some truth in stories made for kids, as they usually aim to instill the values and ideals that we hope they’ll grow up with. My own experience with the void, however, was anything but lighthearted, and loneliness was a very real companion for a very long time. I kept convincing myself that I could escape it by getting new jobs, or by moving to yet another city, or by finding a romantic relationship, but I couldn’t outrun it any more than a dog can outrun his tail. The darkness inevitably came, and it wasn’t until I started trying to understand it that it began to clear. “There must be some kind of way out of here”, I remember playing over and over in my head, because sadness always seems to have the best soundtrack.

I briefly thought about taking antidepressants after finding myself one day sitting on my bed with a sense of hopelessness that didn’t feel normal. A few days later, a psychiatric evaluation concluded that I indeed had depression, and I was prescribed sertraline. That’s the simplified version, but the full story could have been pulled from the opening of a Kafka novel: a yawning Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner robotically asking questions out of a checklist and forgetting she had asked them; a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder after a 30-minute video call; a prescription for Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, ready for pickup within a couple of hours. In hindsight, maybe this cold approach and complicated language were a good thing, like two warning shots fired into the air giving me time to reconsider and run away. It became clear that I wasn’t a patient, just someone on the line with a customer service representative following a script. I might have gone along with it, if I hadn’t heard Carlin immediately yelling in the background: “It’s all bullshit, and it’s bad for ya.”

I don’t mean to disparage depression, a disease that makes the well seem so deep that the very notion of climbing out doesn’t exist. I’ve seen the noonday demon in loved ones and witnessed how it robbed them of their vitality. I know several people who attempted suicide and have heard of others who succeeded—despite the appearance of having everything. While I never contemplated self-harm, I sometimes reflected on how a state of not-being wouldn’t be such a bad thing. It‘s troubling that cases seem to be increasing, and it’s a good thing that science can rescue lost souls if needed. I just knew—or figured out along the way—that I wasn’t one of them. Not this time, at least. I remember thinking that a medication that promised to make me feel better after making me feel worse didn’t make sense, as though I needed to be punished for the insolence of wanting to be saved.

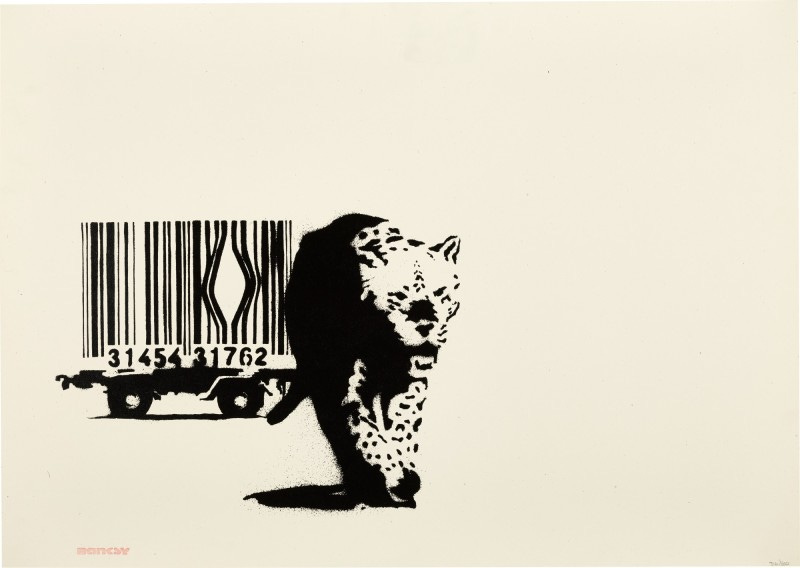

The course of treatment for me was to realize that being affected by a depressing reality isn’t an abnormal reaction, that “it is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society,” as Krishnamurti noted. I didn’t need to bury it but to hold it up to the light and look for the watermark. I eventually found, a couple of years before reading his book, what Frankl called the existential vacuum—a lack of meaning in life that consumes everything. I can’t say that I know where it is yet, but it’s increasingly clear where it isn’t. It isn’t in infinitely scrolling for dopamine hits on social media. It isn’t in binge-watching another TV series with little to no edifying value. It isn’t in constantly buying new things destined to become trash. And it certainly isn’t in company meetings discussing advertising spends of millions of dollars, where the only return on investment is more wealth inequality and a contribution to the linear materials economy that’s destroying everything.

I still don’t know what to do with this newfound compass—not because I doubt its calibration, but because the north that it points to is cold, and the night dark and full of terrors. In a way, my father’s house is helping with that journey, standing like a foghorn guiding ships around rocky waters. It’s comforting when there’s people around, but it’s especially enlightening when the quiet makes space for the non-humans. There’s inspiration to be found in the birds chirping around the breadcrumbs from breakfast, or in the bees showcasing what meaningful work looks like, or in the snails demonstrating the value of slow motion. The vegetation grows effortlessly in the yard, even that which wasn’t supposed to, like the orange tree that was once cut at the base and unexpectedly regrew, starting to bear fruit again. The palm trees in California will always evoke happy memories, but there’s a sense of communion here that was hard for me to find in the Cadillac Desert.

Unlike my siblings, I spent almost no time here when I was younger, so I’m only now beginning to imprint on this place. The figure of my father is absent, but I’m still caught in the trajectory he set, as if he traded taking care of me as a child for the safety that he now provides. It doesn’t feel like home—I’m not sure it ever will—but it does feel like a sanctuary, as much a refuge for the living as a monument to the dead. Pictures of him and of extended family are scattered throughout the house, paintings that he and his artist friends created cover the walls, and books—hundreds of them—enshroud the living room from floor to ceiling. Some of them recent, others written a long time ago, a few in languages that he didn’t even speak. I think he saw books not only as practical items but also as artifacts, memories of the past that are often forgotten and not translated into lessons for tomorrow.

My admiration for him has grown in absentia, as it would for one’s favorite author. He was an interesting and cultured man, evident in how he lived his life and reaffirmed by those who knew him well. He came of age in a different time, during a dictatorship that saw him imprisoned and tortured for a few months for his actions against the state. Being deprived of freedom solidified his belief that to be alive is to necessarily be political and engaged with the world. He understood that there would always be those disposed to trade harmony for hostility, merchants of suffering who see peace as expendable in their quest for power. I don’t miss him so much as I selfishly wish that he had lived longer so I could hear his thoughts on the world today, which I think he would find disappointing, even if not surprising. As a revolutionary, he might have insisted that a different way is possible, so long as there are those willing to fight for it; as a disillusioned ideologist, maybe he would have conceded that the decline of modern society feels inevitable, given its palliative state.

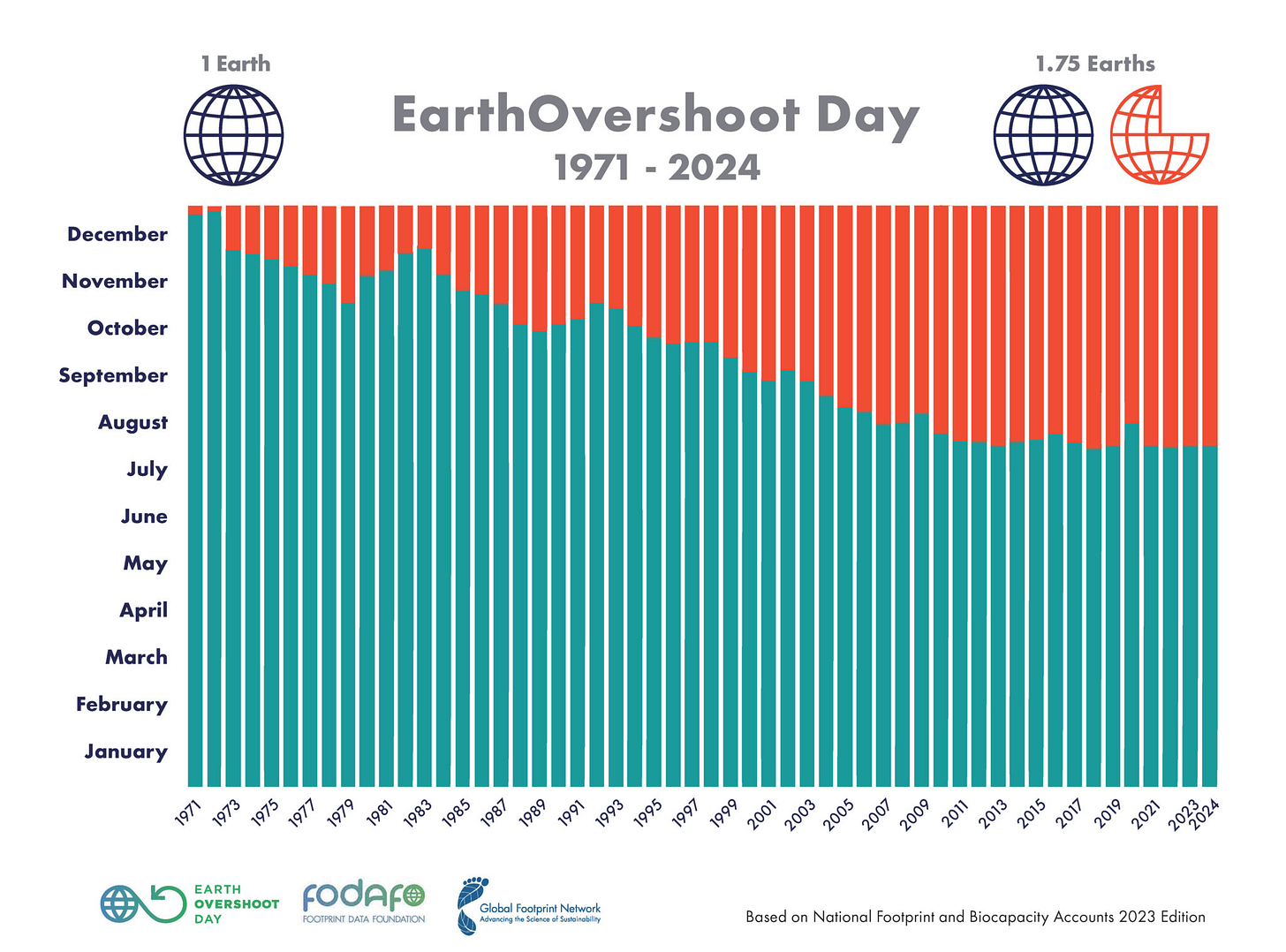

How else would he make sense of the tripling of resources extraction after knowing that the environment hasn’t been replenishing them fast enough since the seventies. How else would he explain to people and governments that infinite growth in a finite planet is a contradictory and self-terminating idea, and that taking action against those who promote it is “the most sacred of the rights and the most indispensable of duties”. It’s a logic that seems increasingly difficult to acknowledge the more successful one becomes within the structure. No politician will garner popular support by advocating for limits; no businessman will accept the real cost of sustainable products; no comfortable person will make their life significantly less so given the choice. Those who try don’t win elections, don’t build thriving companies and don’t attract a lot of friends.

Questions like these may come across as disingenuous when the very act of asking them highlights a privilege denied to so many. They’re not directed at the victims, they’re not necessarily directed at anyone, I suppose they’re more of a distress signal hoping to reach a collective intelligence that feels increasingly eroded. The goal is always more, even for those who already have plenty, and its consequences are always unseen, particularly by the ones who most need to witness them. And so the perversity of the system continues, assured and undisturbed, a real and tangible tragedy where winning inevitably means that everyone loses. It’s a double bind we can’t seem to escape, a mind prison with no walls and no guards that we all willingly maintain against our own future interest.

”What we cannot ignore is that exponential growth—whether you’re a businessman or a government—works, at least in the short term. Fortunes have been made and government budgets have been funded. And if you even sniff of an economic system that is beginning to slow the growth rate, much less shrink, all kinds of bad things happen, beginning with recessions and unemployment. To use a financial term, we’re leveraged to growth in more ways than we realize. I think that some of the conversation about degrowth and limits to growth kind of ignores that reality, that the system demands it to stay a system. So that’s one bind: we’ve got to keep growing. And then the double bind is that if we keep growing we’ll collapse, not only the economy but the ecology and civilization as we know it.”

John Fullerton, in The Great Simplification podcast, episode 149: New Economic Paradigms, Living Systems and Holistic Thinking

Like my father, I try to avoid most kids most of the time. Their usual restlessness alone would be reason enough, but there’s a deeper discomfort that extends beyond physical exhaustion. Their gaze is unsettling, and it feels like I have to try extra hard to impress them, or they might see through the mask. I know they’re learning how to be in the world, but that’s a responsibility that I’m not eager to take on. They ask questions that I don’t know how to answer and look for guidance that I don’t know how to offer, partly because I disagree with many of the premises they’ve been given in the first place. “Why do you need to get good grades? I don’t know, why do you? Maybe you don’t. Maybe you shouldn’t have to.” It’s a kind of approach unlikely to win much sympathy from their parents, so I end up reinforcing the same outdated stories that keep conscripting future generations into a broken humanity. I have to pretend that my worries shouldn’t be their worries—as if they’re not the ones who will primarily live through them—and I find it hard to be interested in theirs, so I prefer to keep my distance.

Lately, however, I’ve been reframing my issues with youth, as I’ve been finding myself more frequently surrounded by it. Sons and daughters of friends and family, from different age groups, with different interests and concerns, based on different educations and parenting styles. The younger ones are often smarter and more knowledgeable than I’d give them credit for, and some of the older ones are already seeing through the deception and calling out the basic truths about the status quo—how unjust it is, how unsustainable, how unacceptable. It’s an inspiring rage that hopefully won’t turn into the conformity and resignation that I see in so many around me, so often in myself.

It turns out that the young people are fine—it’s the adults who shape them that I have a problem with, especially those who champion children as the future yet rush to shut them down the moment they try to reclaim it, accusing them of being too loud and their methods too crude. There’s indeed something to be said about effective activism, but most criticism seems aimed solely at silencing the dissenters, the voices who would have us face our complicity with the atrocities. Some of these kids eventually relent under the weight of so much opposition, but some keep going, maybe because they’ve realized that the only way forward is through. I think back to when I was their age and remember how little I thought about such things, how submerged I was in the illusion of separation. I continue to unlearn it, to try and deconstruct those virtual borders, to remind myself that the map is not the territory.

As an architect, my father was used to accurate representations of the physical world. As an artist, perhaps he sought to express the intangibility that his blueprints and models couldn’t. Maybe as a dad he could’ve taught me about that interdependence and shown me more elegantly structured perspectives of reality. In some ways, I think he’s doing just that.

Beautiful 🪁